collected thoughts on Aria Dean's Abattoir, U.S.A.!

this is technically an older essay I wrote months ago (Jan 2024) and then unpublished but I need it up again to reference in the essay that I'm currently working on, so...

“And so it goes...”

― Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

I went to see Aria Dean’s short film Abattoir, U.S.A! for a first date recently. Probably not the best film choice for a first date in retrospect, but ultimately hindsight is 20/20, and they seemed cool with it. I think that had it not been for trying to impress an attractive stranger by not acting like a complete weirdo on a first date, I could have sat in that dark rubber-floored room and been drawn into Abattoir, U.S.A.!’s unreal thrall for hours.

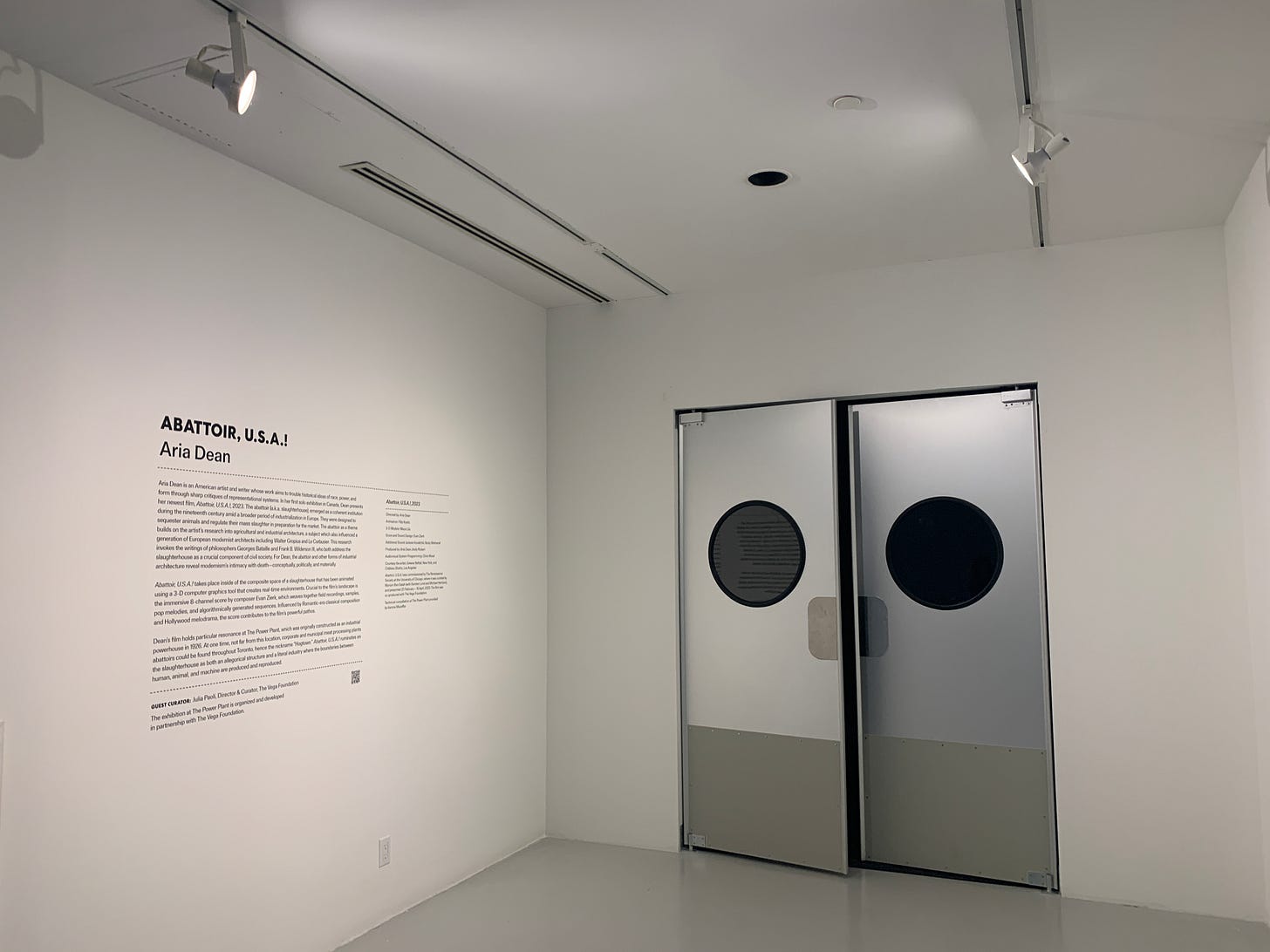

The short film, created by Dean using Unreal Engine, a 3D computer graphics tool, depicts an empty slaughterhouse, or abattoir. It begins by panning down from a glass ceiling into the empty pens of a slaughterhouse, taking the viewer through a track towards the simulated slaughter of the artificial specter from which we witness the abandoned abattoir. The ‘slaughter’ itself is a departure from the cold grey industrial sheen of metal and glass that precedes it, as flashes of amber rush iris and sundog-like across the screen. The incorporeal viewer awakens from the perspective of lying in a pool of blood — can it truly die? — as the very same doors that welcomed you into the screening room violently swing open and into an empty meat locker lined with swaying hooks. The score (by composer Evan Zierk) swells into an instrumental rendition of I Think We're Alone Now (a banger). The screen fills with shimmering blood. Credits roll.

I don’t particularly believe in the Hollywood version of ghosts, or of Paranormal Activity-esque boogeymen, but I do believe that places can collectively store energy, and can collectively store trauma. You can feel it. Some places are haunted. The unseen ‘protagonist’ of Abattoir, U.S.A.! cannot possibly be human. We follow its gaze as it floats and twists and jerks its way through the slaughterhouse in inhuman and unnatural pathways. Although the space is empty, it is unclean. There is clear evidence of prior slaughter; hay and grass line the floors trampled into the mud, the twisted metal rusting from use, and the pools of blood on the concrete floor are still slick and shiny. The blood has not even had a chance to dry yet.

It feels apocalyptic, reminiscent of one of those video games (especially due to the 3D computer graphics, which feel just realistic enough to kiss the uncanny valley but unreal enough to disorient) where you wander through a bombed-out nuclear site looting homes. We know exactly what happened here, except for why it stopped. Where did everyone disappear to, and why so quickly? All that remains is trauma. Our unhuman unseen protagonist is doomed to loop through the humdrum banality of horror for eternity, never truly being slaughtered permanently. And so it goes…

From Wikipedia — in economics, an externality is an indirect cost or benefit to an uninvolved third party that arises as an effect of another party's activity. For example, from the late ‘60s to the early ‘80s, the Ford Motor Company dumped hazardous waste from its automotive plant into the land of the Ramapough Mountain Indians. The future failing health of their community was an externality to the machinations of industry and profit for the Ford Motor Company.

Through Abattoir, U.S.A.!, Dean forces her viewer to contend with the externalities of American imperialism and racial capitalism. Afropessimism contends with our society’s continued reliance on anti-Black violence. In Erika Balsom’s Artforum piece on Abattoir, U.S.A.!, she raises Frank B. Wilderson III’s “cow question” from his 2020 book Afropessimism.

We must ask, what about the cows? The cows are not being exploited, they are being accumulated and, if need be, killed. The desiring machine of capital and white supremacy manifest in society two dreams, imbricated but, I would argue, distinct: the dream of worker exploitation and the dream of black accumulation and death.

— Frank B. Wilderson, Afropessimism

Dean’s abattoir is not of the sublime, not an artificial rendering of some alien terrain but a visceral reminder of the machinations of the prison industrial complex, of the continued dehumanization and otherization of racialized peoples both in America and internationally.

Capitalism and our civil society are structured upon the brutalization of Black people. When Dean creates this empty slaughterhouse, leaving us without the products of our destruction and only with the machinery to create it, we are left with something both entirely human and yet external from humanity. Utopia means “nowhere.” This dystopian scene Dean crafts in Abattoir, U.S.A!, is both nowhere (simply a 3D rendering) and everywhere, surrounding us in everyday life.

Dean was initially inspired by philosophers Georges Bataille and Frank Wilderson, each of whom address the slaughterhouse in their writings—whether as a metaphor or paradigm—as crucial to the constitution of civil society.

— Abattoir, U.S.A.!, Aria Dean, The Power Plant exhibition description

Consider the slaughterhouse as crucial to the construction of civil society. Everyone knows what happens in a slaughterhouse. Contrary to the infamous Paul McCartney quote, we have seen everything. Everyone knows what happens in a sweatshop, what happens when we tear down homeless encampments, and what happens when we bomb a country overseas for its natural resources. We just don’t want to bear witness. The slaughterhouse is crucial because it hides our brutality. We can act civilized. We can wear our cheap fast fashion clothing, drink our $7 lattes on an anti-homeless architecture bench, turn off the news, and burn fuel in our cars while people are dying somewhere else.

When I think of the humdrum banality of products resulting from the horrors of capitalist production and exploitation, I generally think of two things. The first is the following Sally Rooney quote:

I was in the local shop today, getting something to eat for lunch, when I suddenly had the strangest sensation – a spontaneous awareness of the unlikeliness of this life. I mean, I thought of all the rest of the human population – most of whom live in abject poverty – who have never seen or entered such a shop. And this, this, is what all their work sustains! This lifestyle, for people like us! All the various brands of soft drinks in plastic bottles and all the pre-packaged lunch deals and confectionery in sealed bags and store-baked pastries – this is it, the culmination of all the labour in the world, all the burning of fossil fuels and all the back-breaking work on coffee farms and sugar plantations. All for this! This convenience shop! I felt dizzy thinking about it. I mean I really felt ill. It was as if I suddenly remembered that my life was all part of a television show – and every day people died making the show, were ground to death in the most horrific ways, children, women, and all so that I could choose from various lunch options, each packaged in multiple layers of singe-use plastic. That was what they died for – that was the great experiment.

— Sally Rooney, Beautiful World, Where Are You

The second is Kapwani Kiwanga’s Remediation, which I went to see at the Museum of Contemporary Art in June of 2023. Specifically, Elliptical Field. The installation piece is these towering suspended disks lined with a sheep’s wool-like substance, at once both earthily animal fur-esque and plantlike yet impossibly alien in their appearance. Behind the disks, a great curved wall of the stuff pours over itself onto the MoCA’s concrete floor. The substance is made from sisal, a fibre harvested from Agave sisalana.

Kiwanga describes seeing large plantations of sisal in Tanzania, where her paternal family resides. Agave is not native to Africa and was first brought illegally to the continent by German plantation owners who began to develop the crop on a large scale.

— Kapwani Kiwanga: Remediation, MoCA exhibition booklet

Germany oversaw a violent quashing of the Tanzanian anti-colonial rebellions that resulted in the massacre of hundreds of thousands of people. In the contemporary era, the Tanzanian government is still seeking reparations from Germany, with little concrete action from their former colonizer.

When you look at it, this heaping mound of beige matter or shelves of various chocolate confectioneries, and think about all the human suffering and destruction and slaughter and pain that it took to create some product, it feels absurd. Pointless and pathetic.

But I digress.

One of my favourite films is the 1974 version of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Outside of the joys of watching a chainsaw fight, I despised the 1986 sequel. This was because Leatherface suddenly had a sexual desire for the final girl, which I felt humanized him; to desire pleasure and human connection. The entire horror of the original stems from the antagonists’ inhumanity, their desire for nothing more than grotesque violence for the sake of it. They were a slaughterhouse made flesh.

What is left of capitalism without people? We created something new, something unhuman. What will it do to us?

I’m reminded of Hito Steyerl’s This is the future, which I saw at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2019. Specifically, the piece Hell Yeah We Fuck Die (2016), within it a video compilation of robot technology testing labs, where robots are brutalized in the name of progress. Of course, the robots are inhuman and thus not subject to pain — right? But what are they learning of humanity? What future are we building for ourselves?

I recently attended Renditions, an art night hosted by New Currency, where a panelist quoted from essayist Katherine McKittrick’s writings on theorist Sylvia Wynter, saying that “through such creative acts we find the poetics of our future.” As we build white supremacist artificial intelligence and commodify art into ‘creative-type’ blandness, I have to wonder what the poetics of our future will be, if these are the creative acts we are currently undertaking.

As you leave the dark screening room of Abattoir, U.S.A.!, you realize that you entered through those very same slaughterhouse doors.